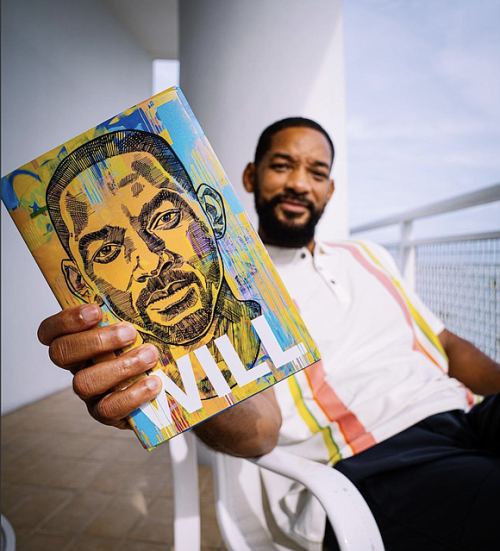

In Will Smith’s memoir, the superstar is self-deprecating but ultimately invincible

Smith was an excellent student. “I was never promoting a movie,” he writes in his new memoir, “Will.” “I was using their $150,000,000 to promote me.” The result: astronomical success. In a Hollywood — and a music industry — that was even Whiter than it is today, Smith’s bankability was without precedent or rival. “Men in Black” and “Enemy of the State”; Oscar nominations for “Ali” and “The Pursuit of Happyness”; an unequaled golden run, from “Men in Black II” through “Hancock,” of eight consecutive movies grossing more than $100 million. A quarter-century after Planet Hollywood, it’s hard to imagine a shrewder move than publishing a memoir the same month you release your biggest Oscar contender in years (the tennis drama “King Richard”).

As most candidates know, a little vulnerability is also a vote-winner. And thus: “What you have come to understand as ‘Will Smith,’” he writes on Page 1, “the alien-annihilating MC, the bigger-than-life movie star, is largely a construction — a carefully crafted and honed character — designed to protect myself. To hide myself from the world. To hide the coward.” This is the story Smith wants to tell about his life: that of a fierce drive for success rooted in powerful feelings of inadequacy. Unfortunately, what feels like real anguish — and the seed of a worthwhile read — is repeatedly obscured by braggadocio and pat moralizing.

Willard Carroll Smith Jr. was, like the song says, in West Philadelphia born and raised. His middle-class childhood was one “of constant tension and anxiety,” lived in fear of a violent alcoholic father. Young Will developed the emotional acuity that would serve him as an actor out of necessity; “a missed glance or misinterpreted word could quickly deteriorate into a belt on my ass or a fist in my mother’s face.” After one of Daddio’s assaults on his mother, when Smith was 13, he considered suicide.

After meeting DJ Jazzy Jeff he decided, against his mother’s wishes, to ditch plans for college (Smith was good at math and science) and try to be a hip-hop star. The duo’s first hit dropped before Will had even graduated and he never looked back. He became the first rapper to win a Grammy. “Fresh Prince” ran for six seasons. His film career is the stuff of legend.

There were errors, including a tax snafu that left him with huge debts to the IRS, and he’s candid about parenting and marital mistakes (if coy about his and Jada Pinkett Smith’s reported nonmonogamous dalliances). Yet despite the book’s self-deprecating setup, it’s Will the Invincible who shines. Writing about the inspiration that produced “Summertime”: “Skeptics call it self-delusion; I call it ‘another Grammy’ and ‘my first #1 record.’ ” On the period following “Independence Day”: “an absolute, unadulterated, unblemished rout of the entertainment industry.” Prideful statements like these pump out of Smith like an oil spill in a sea of good intentions.

Perhaps this is just his way of demonstrating the “overcompensation and fake bravado” that, he says, “were really just another, more insidious, manifestation of the coward.” But such clunky teaching moments are overshadowed by the megalomaniacal ambition and greed on display. After “I Am Legend” broke box office records for a December release, he wondered what could have made it more successful. After Jim Carrey became the first actor to pocket $20 million a movie, “the conversation with me started at . . . twenty-one.” (Even when he plays his kids at Monopoly, it’s to win.)

Smith’s choice of writing partner, Mark Manson — author of the bestseller “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck” — implies a desire to hold up his life as a model of sorts. Most chapters contain some hokey self-help boilerplate to signpost learning — “I’d conflated being successful with being loved and being happy,” etc. But these nuggets feel so precision-engineered to showcase Smith’s hard-earned self-awareness that they appear trite, even insincere, when juxtaposed with his riotous magniloquence. The result is half-baked: real epiphanies bypassed; lessons unlearned. The book ends with a charity heli bungee jump over the Grand Canyon for Smith’s 50th birthday — an act of philanthropic egoism that perfectly embodies the unresolved tension between his savior impulse and an insatiable need to be The Man.

In 1993’s “Six Degrees of Separation,” Smith plays a con artist who woos a wealthy couple by pretending to be the son of Sidney Poitier. Even after the couple wises up, the attraction, at least for the wife, remains. Finally, something similar occurs in “Will.” You like him despite the evident calculation at play: His foundational insecurity is part of his appeal; even while consciously selling his own vulnerability, he inadvertently reveals its true depths. And so, despite “Will” feeling more like part of a corporate strategy than a work of real introspection (even the acknowledgments redirect you to Smith’s Instagram), you’d probably still vote for him.