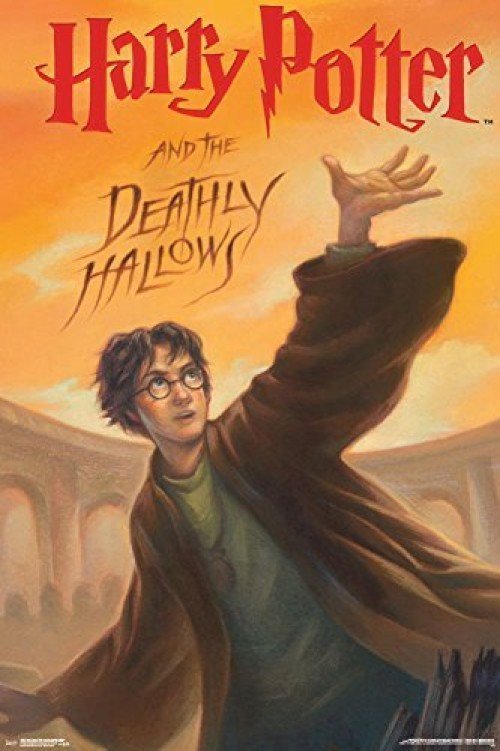

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by JK Rowling review

Harry Potter's final adventure may have revealed many secrets and answered long-unanswered questions, however one mystery still remained: why was Hogwarts' Eloise Midgen such a "martyr to acne"? Despite the wizarding world renowned for its magical cures - from regrowing bones to complex orthodontics at a wave of the wand – this specific cure remains just out of reach.

JK Rowling has captivated readers with her intricate world of wizards, witches and magic. At the center is Voldemort - a menacing entity representing pure evil that's growing increasingly powerful in his quest to defeat Harry Potter. As we reach book seven, it seems almost inevitable that one day he will succeed in taking over Britain entirely with terrifying authority; non-magical people are already being its victims by facing interrogations from 'pure bloods' before potentially being sent off for imprisonment at an unforgiving wizarding camp. But all hope is not lost... along comes 17 year old Harry ready to fight against these dark forces.

To anyone unacquainted with the epic so far, the latest tale will be incomprehensible. In earlier volumes, Rowling made heroic efforts to initiate new readers, but since this process would now require, at a minimum, a glossary, rule book and catalogue of magical objects, she seems to have given up the task as hopeless. But some regular readers may also be disconcerted by a tranche of Hogwarts in which there is neither Quidditch nor lessons. All the familiar Harry scenes have gone missing, from the inaugural, always comforting comedy inside No 4 Privet Drive and the annual bullying bout on the Hogwarts Express, to Mrs Weasley's Christmas jumpers and - more mercifully - Hagrid's inevitable adoption of some tiresome magical creature whose assistance will later prove critical. There was a time when you could set your clock by it.

To go into detail about the questing and battles that have replaced the usual timetable would probably be unfair: even a week after publication there may still be one or two children as innocent of Harry's fate as the American crowds who gathered at the New York harbourfront in 1841 to ask disembarking passengers from England, "Is Little Nell dead?" But only Quidditch fans could complain about the outcome: Rowling has woven together clues, hints and characters from previous books into a prodigiously rewarding, suspenseful conclusion in which all the important questions, including the true nature of Severus Snape, the fates of Crabbe and Goyle, and the presence of the dark wizard Grindelwald on a Chocolate Frog card in book one, are punctiliously resolved.

The author was surely right, on the eve of publication, to implore journalists not to spoil the surprise for a generation who have enjoyed something unique in children's literature (where the characters tend to stay the same age, like William Brown, or, if they do mature, to do so as hobbits, Romans or Aslan worshippers): a chance to grow up, in real time, with their heroes. But Rowling was duly accused of colluding with a ruthless marketing operation, which led to 2m copies of her book being sold within 24 hours of publication.

Although her sales techniques do contrast sharply with arrangements in Harry Potter's Nintendo-free world, it is curious that Rowling should be so harshly judged for her engagement with the book trade. Didn't most eminent Victorian novelists fight just as greedily for their profits, become, in several cases, international celebrities, and see their better cliffhangers and denouements stimulate the nation into moments of collective delirium?

But as her critics point out, Rowling is no Dickens. That the welfare of Harry Potter should, each year, become a question of national importance has only deepened a suspicion, in some quarters, that Rowling's writing is not merely mediocre but contaminated by her participation in a crass celebrity culture. In 2000, Harold Bloom despaired for her readers. "In an arbitrarily chosen single page - page 4 - of the first Harry Potter book", he objected, "I count seven clichés, all of the 'stretch his legs' variety".

Professor Bloom had his work cut out for him, tallying the thousands of cliches in J.K Rowling's ongoing series. The books have grown longer by the volume with a continuous onslaught of simple phrases and descriptions to portray an enraged Harry Potter who would show -and tell- his anger without fail! If only some trimming had been done on paragraph repetition and frequent angry utterances from our hero , perhaps 10 thousand trees could've been saved.

J.K Rowling has created a remarkable, jaw-dropping fantasy world with countless unique characters, places and magical spells woven together by her extraordinary wit and energy. Her books offer an incredible assortment of surprises - from unexpected plot developments to unforeseen subplots that keep us gripped until the very last page! It's truly a masterful achievement in fiction that continues to captivate fans across the globe.

Those who, as children, dreaded having to leave the lovable and exciting worlds of their favorite books may envy J.K. Rowling's unparalleled gift for creating a unique universe that expands by hundreds of pages with each passing year; one so meticulously detailed that her readers can almost immerse themselves in it while they eagerly await new discoveries every twelve months.

Rowling weaves a magical, captivating tale that is alluring for both younger and older readers alike. Through her characters she reveals an admiration of youths' sentimentality towards budding relationships, their naive political thoughts, and even their choice words such as "toerag". In the new book it falls on the teenagers to rescue generations from Voldemort's malicious intent - ultimately caused by bigotry rooted in adults against those deemed lesser than them; orcs gnomes and house-elves included.

As well as saving adults, Harry the freedom fighter subjects them to homilies, in which he urges remorse, courage, good parenting: "Parents", Harry tells an errant father, "shouldn't leave their kids unless - unless they've got to."

Harry's task is a poignant lesson, but Ron lightens the somber atmosphere with his acerbic comments. Just as Harry attempts to connect with an elf who has been mistreated, Ron interjects and reminds him that perhaps he was taking it too far - his reminder providing comic relief in what could have otherwise become maudlin.

It is a key element in Rowling's own myth that she plotted the entire Potter series before she started, and on its completion, you can see that the protagonists, the principal families and their allegiances, the design of Hogwarts public school, and the grand plan for a final confrontation between goodness and badness were, as alleged, always in place. But since book three there has been more and more evidence of (occasionally helpless) ad hoc-ery. Everything must have changed once it became clear to Rowling and her publishers that her readers - adults as well as children - would gobble up as much Potter as she could bear to produce. Hence such things as the tri-wizard tournament and an excursion to Downing Street to meet a Muggle prime minister whose original has also disappeared without trace. Even the newly arrived Hallows, some nifty plot accessories that allow for all kinds of crises, personal challenges and protracted revelations, point at a desperate struggle, once Rowling had arrived at the middle of the last book, to hold off the final act.

By itself, the cheeky Hogwarts motto (Draco dormiens nunquam titillandus) that ornamented the title page of The Philosopher's Stone is enough to suggest that Rowling did not, back in 1997, plan to end her series with a protracted meditation on death, prefaced by a few lines from Aeschylus: "Oh, the torment bred in the race, the grinding scream of death." The Potterati, scanning the text for learned allusions (and there are plenty, from Dante and Orwell to Jesus Christ and Tinky Winky), may well see in its genocidal, dystopic shadows the intrusion of a real world that became, not long after Harry Potter arrived in it, a far more frightening place. But the book's resounding melancholy may derive from something simpler. Whatever happens in the last of these brilliant adventures may matter less, for the millions of children who grew up with Harry Potter, than the end of his companionship and with it, the end of their childhood. Which is a much more wholesome story than Peter Pan's, but sad, all the same.